Overbuilding the Future: Why AI Is Repeating the Railways and Dark Fiber Cycle

Highlights

- AI is entering a classic investment–crash–digestion cycle, the same pattern seen in railways, electrification, and the dot-com fiber boom.

- Firms face a strategic dilemma: overbuild now and risk idle assets—or wait and risk being locked out by competitors with superior scale.

- As corporates opt for overbuilding data centers and power capacity ahead of demand, they accept temporary low utilization as the price of securing scale and first-mover advantage.

- Despite a painful mid-phase, historically the long arc has been constructive. The period of idle capacity is followed by demand “digesting” the slack and accelerating productivity.

- Surviving builders typically emerge with infrastructure advantages competitors can no longer replicate.

The Investment–Crash–Digestion Cycle: A Familiar Pattern

When a transformative technology arrives, it almost always triggers an investment–crash–digestion cycle. Corporates face a strategic bind: the only way to secure scale, network effects, and first-mover advantage is to build ahead of demand, even if that means risking years of idle capacity. Underbuilding is an existential risk; overbuilding merely hurts. Thus, some firms opt for– hopefully – temporary pain instead of risking being left out of the new market.

In the early phase, greenfield capacity expands far faster than actual adoption (i.e., the Investment phase). In a rush to be first movers, gain scale, and crowd the competition out of the nascent industry, firms deploy large amounts of capital in greenfield projects to host the new technology. Usually, this cycle is accompanied by a rapid expansion of available capital, whether equity, debt, or hybrids, which funds this fixed asset formation phase.

However, this accelerated supply capacity outpaces demand formation, leading to a glut of idle capacity (i.e., the Crash phase). With utilization rates falling well below projections, balance sheets stretch, and project economics are diluted, leading to a rapid correction in market valuations.

Nevertheless, the final act is usually constructive as demand slowly eats away the slack (i.e., the Digestion phase). Given that the available capacity is a sunk cost for the supplier, producers align their prices with the variable cost of production, leading to drastic price reductions. As a result, productivity across all sectors in the economy expands, and the survivors emerge with infrastructure that competitors can no longer afford to replicate.

This is how modern infrastructure gets built, and AI is now following that script at unprecedented speed and scale.

Historical Rhymes: When Capacity Surged Ahead of Demand

1. The Railway Manias (UK 1840s; US 1860s–70s)

The railway boom of the nineteenth century remains the archetypal investment–crash–digestion cycle.

Railways were the first true general-purpose infrastructure of the industrial age. They collapsed transport costs, rewired labor markets, enabled national supply chains, and reshaped urbanization. Recognizing their transformative potential, investors and entrepreneurs raced to build rail networks at a pace far ahead of immediate economic demand.

In Britain during the 1840s, speculative fervor culminated in “Railway Mania.” Parliament authorized thousands of miles of new track, often with overlapping or redundant routes. Capital flooded into railway shares, driven by the belief that traffic growth would inevitably justify almost any line. Construction surged, but passenger and freight volumes lagged. By 1846–47, utilization rates fell short of expectations, profitability deteriorated, and railway equities collapsed. Investors suffered heavy losses, while many lines operated at or below breakeven for years.

A similar dynamic unfolded in the United States after the Civil War. Railroad mileage expanded explosively as promoters sought to knit together a continental economy. Lines were pushed westward ahead of settlement, financed by bond issuance, land grants, and optimistic projections of future freight. By the early 1870s, capacity far exceeded near-term demand. When financing tightened and revenues disappointed, the system snapped. The failure of Jay Cooke & Co. in 1873, deeply exposed to railroad bonds, triggered a financial panic. Dozens of railroads entered bankruptcy, bondholders were impaired, and equity was largely wiped out.

In both countries, the crash was financial, not physical. Tracks, stations, and rolling stock did not disappear, they became stranded assets with sunk costs on overstretched balance sheets. Over the following decades, bankrupt lines were reorganized, consolidated, and refinanced at lower capital costs. As industrial output grew, populations urbanized, and commerce intensified, traffic volumes steadily rose to meet the installed network.

By the late nineteenth century, railways, many of which had been derided as speculative folly at inception, formed the backbone of national economies. The excess capacity of the boom years was digested and enabled faster growth, lower transport costs, and deeper market integration than would otherwise have been possible.

2. Urban Electrification (US 1920s)

The electrification boom of the 1920s offers a subtler—but highly instructive—version of the investment–crash–digestion cycle.

Electric power is a classic general-purpose technology. In the 1920s, achievements in electrical engineering allowed utilities to build large power generation plants, transmission lines, and urban distribution grids, betting that industrial electrification and household adoption would scale rapidly and continuously. Capital spending surged as utilities competed to secure exclusive service territories, long-term industrial customers, and urban density advantages.

By the late 1920s, much of the physical grid had been built ahead of realized demand. Generation capacity expanded faster than electricity usage, and utilization rates quietly slipped below expectations. The financial structures underpinning the sector made matters worse: many utilities were embedded in highly leveraged holding-company pyramids, where modest shortfalls in demand translated into severe balance-sheet stress.

The Great Depression exposed these weaknesses. Industrial output collapsed, electricity consumption stalled, and revenues fell just as fixed costs peaked. While the lights never went out, the economics of the sector deteriorated sharply. Numerous utilities failed, were consolidated, or required restructuring, and investor capital was heavily impaired. The crisis ultimately prompted regulatory intervention, culminating in the Public Utility Holding Company Act of 1935 (PUHCA), which dismantled overleveraged structures and forced balance-sheet repair.

Yet the physical infrastructure survived—and proved invaluable. Over the following two decades, electricity demand steadily absorbed the surplus capacity. Household appliance adoption, factory electrification, air conditioning, and postwar suburbanization drove a sustained increase in usage. By the 1950s, the grids built in the 1920s were running near capacity, supporting one of the most productive economic expansions in history.

The overbuild of the 1920s looked reckless in the crash—but indispensable in hindsight.

3. The Dark Fiber Boom: When Bandwidth Became an Option (Late 1990s)

The fiber-optic boom of the late 1990s is a bit more complex but follows the same investment-crash-digestion pattern. Instead of a single, major technological achievement, the 1990s produced several coinciding hardware, software, and regulatory achievements that removed bandwidth restrictions tied to the physical act of laying cable.

This progress meant that once fiber was in the ground, its capacity could be expanded later by upgrading the electronics at either end. In effect, fiber became an option on future bandwidth, not a fixed pipe sized to current demand. That change radically altered investment incentives.

Telecom operators responded rationally. If most of the cost was in trenching and rights-of-way, the optimal strategy was to lay as much fiber as possible, as early as possible, and assume demand would eventually catch up. Future capacity could be “turned on” cheaply when needed. The result was a construction boom that far outpaced near-term internet usage.

The story felt compelling at the time. Internet traffic was growing exponentially, and it seemed reasonable to extrapolate that growth indefinitely. Carriers raced to build nationwide and transcontinental networks, often duplicating routes, confident that utilization would follow.

It didn’t, at least not on the timetable investors expected. When the dot-com bubble collapsed in 2000, traffic growth slowed, pricing collapsed, and balance sheets buckled under the weight of debt. Vast stretches of fiber went dark, giving the episode its name. Equity holders were wiped out, and debt-holders had to haircut the value of their paper.

What looked like reckless overbuilding in the crash phase proved essential in the digestion phase. The error was not in the technology, but in the timing of demand relative to investment.

AI Today: The Biggest Overbuild of the Century

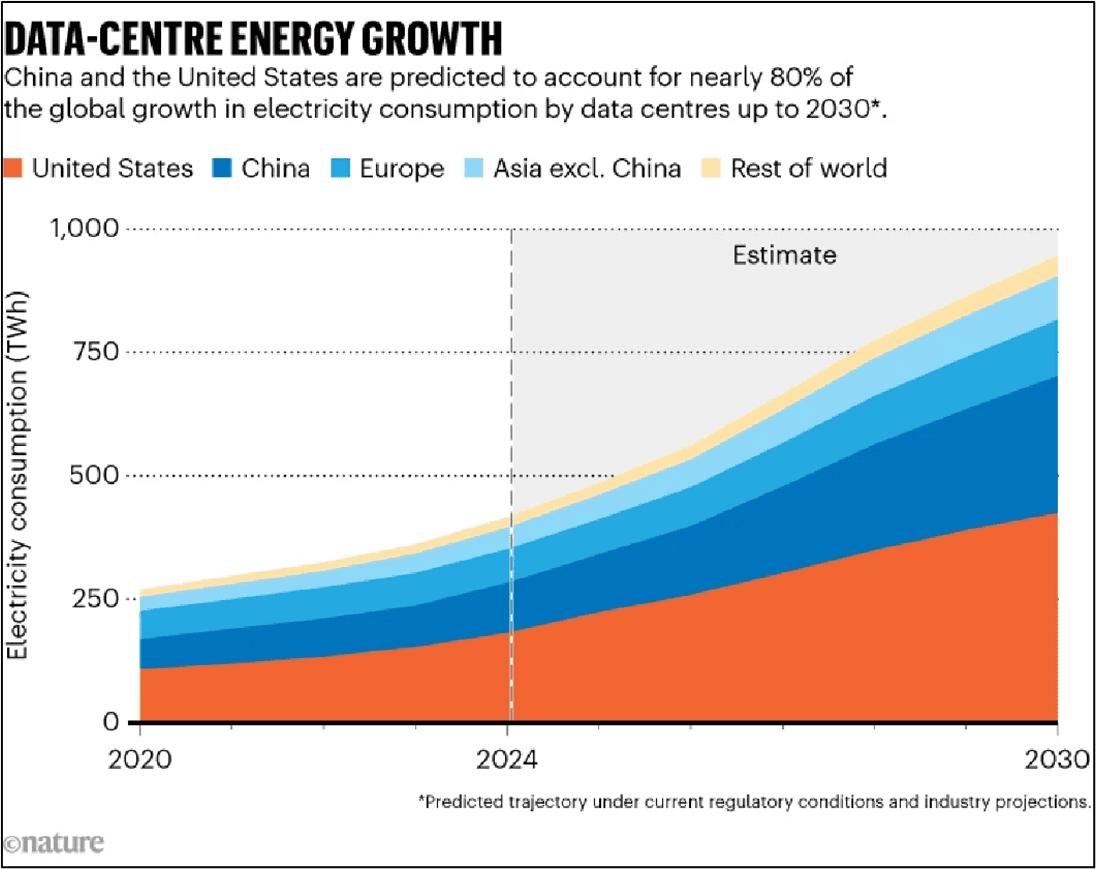

We are living through the next, perhaps largest, iteration of this cycle. AI’s infrastructure boom is bigger, faster, and more resource-intensive than any fixed-asset buildout of the past.

The Investment Phase (Now): A Land-Grab at Unprecedented Scale

Hyperscalers are racing to secure land, substations, transformers, transmission hookups, fiber routes, and cooling and water rights. The capex numbers are staggering:

- Big Tech is on track to spend $350–400bn in 2025 on capex, mostly AI data centers.

- Meta has outlined $600bn of AI-related infrastructure spending through 2028.

- Oracle + OpenAI have floated a $500bn “Stargate” mega-facility.

- US data-center power demand may exceed 100 GW by 2035—equivalent to adding a mid-sized European country’s worth of electricity consumption.

- Each MW of AI compute requires tens of tons of copper, stressing supply chains.

Corporates know the risks: idle GPU clusters, unused substations, stranded megawatts, and rapid obsolescence. But the strategic calculus is simple:

If you don’t build now, you will be locked out later.

The Crash Phase (Ahead): When Utilization Can’t Keep Up

Every historical overbuild ends the same way: capacity grows exponentially, demand grows sigmoidally. Eventually, expectations meet gravity.

AI will likely face a similar moment, and we think it is a question of “when” rather than “if”:

- Training demand may plateau temporarily.

- Enterprise adoption could lag pricing and availability.

- Hardware cycles may outpace real workloads.

- Regional power or permitting constraints could leave capacity idle.

- ROIC will come under pressure, and weaker players could be squeezed out.

The Digestion Phase (Later): When the World Finally Catches Up

Once demand scales into the surplus, the picture changes:

- AI agents, copilots, and workflow automation could permeate everyday enterprise processes.

- Consumer applications may expand inference workloads dramatically.

- Entire industries might shift computation to cloud AI platforms.

- Cheap, ubiquitous computing could unlock new categories, much as dark fiber enabled streaming and cloud SaaS.

By the 2030s, today’s “excess” capacity may look like foresight.

The Corporate Dilemma: Too Much, Too Early—or Too Little, Too Late

Every overbuild cycle forces the same impossible tradeoff:

- Build too early risks idle assets and financial pain.

- Build too late risks irrelevance, locked out by players with superior scale.

The AI investment boom is not an anomaly. Hyperscalers are choosing the only viable path: bet big now, tolerate underutilization, and trust that future demand will digest the surplus. This sits squarely within the historical pattern of investment → crash → digestion, through which every major infrastructure revolution has been financed.

The difference this time is magnitude. Yesterday’s overbuild was rails and fiber. Today’s is computing and power, the two physical layers that AI cannot live without.

© 2025 Securities are offered by Lime Trading Corp., member FINRA, SIPC, & NFA. All investing incurs risk including, but not limited to, the loss of principal. Additional information may be found on our Disclosures Page. The material in this communication is not a solicitation to provide services to customers in any jurisdiction in which Lime Trading is not approved to conduct business. The material in this communication has been prepared for informational purposes only and is based upon information obtained from sources believed to be reliable and accurate; however, Lime Trading Corp. does not warrant its accuracy and assumes no responsibility for any errors or omissions. The information provided is not an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security or a recommendation to follow a specific trading strategy. Lime Trading Corp. does not provide investment advice. This material does not and is not intended to consider the particular financial conditions, investment objectives, or requirements of individual customers. Before acting on this material, you should consider whether it is suitable for your particular circumstances and, as necessary, seek professional advice.